About the Izumo region

The Matsudaira Clan’s Rule in Izumo Province

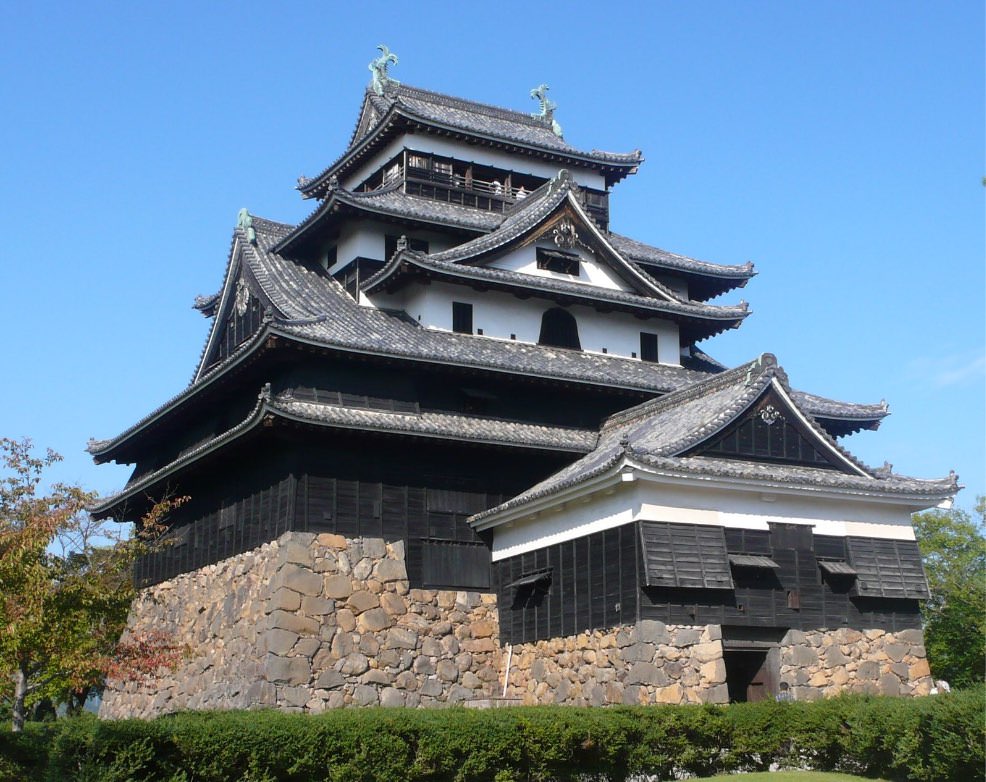

Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868) was an era when the samurai warrior caste ruled as lords over the farmers and townspeople who lived in the villages and towns. In the case of Izumo Province, territorial authority was granted in 1638 to Matsudaira Naomasa, the grandson of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. Rule by the Matsudaira Clan as a cadet daimyō house, which enjoyed favorable relations with the Tokugawa shoguns, continued unbroken for over 230 years, until Japan’s feudal domains were abolished and replaced with modern prefectures. For this reason, a deep relationship was formed between the Matsudaira Clan of Matsue Domain and their subjects, one that has found expression in cultural as well as political and economic terms.

Courtesy of Gessho-ji temple

The Geographical Characteristics of Izumo Province and Its Modern Industries

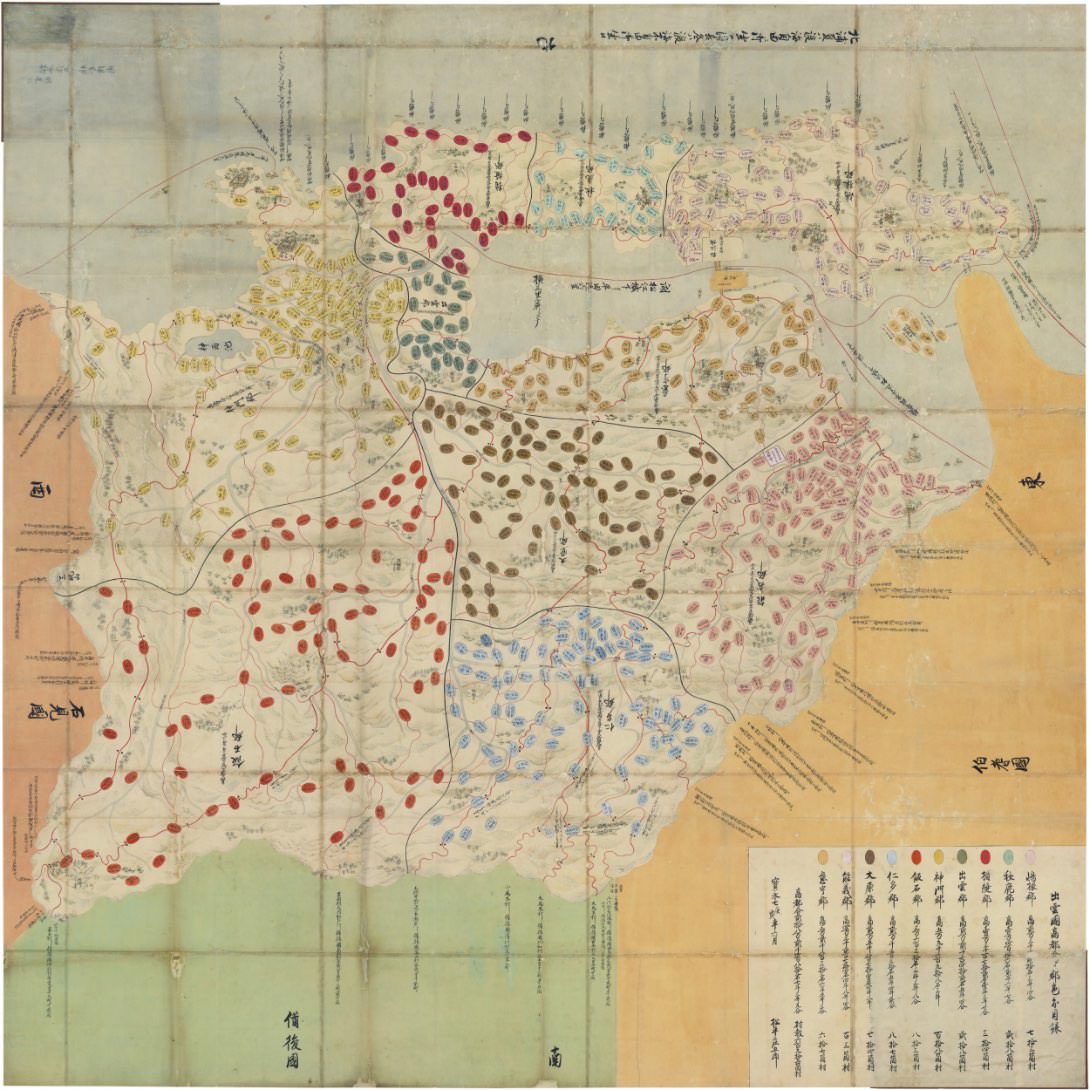

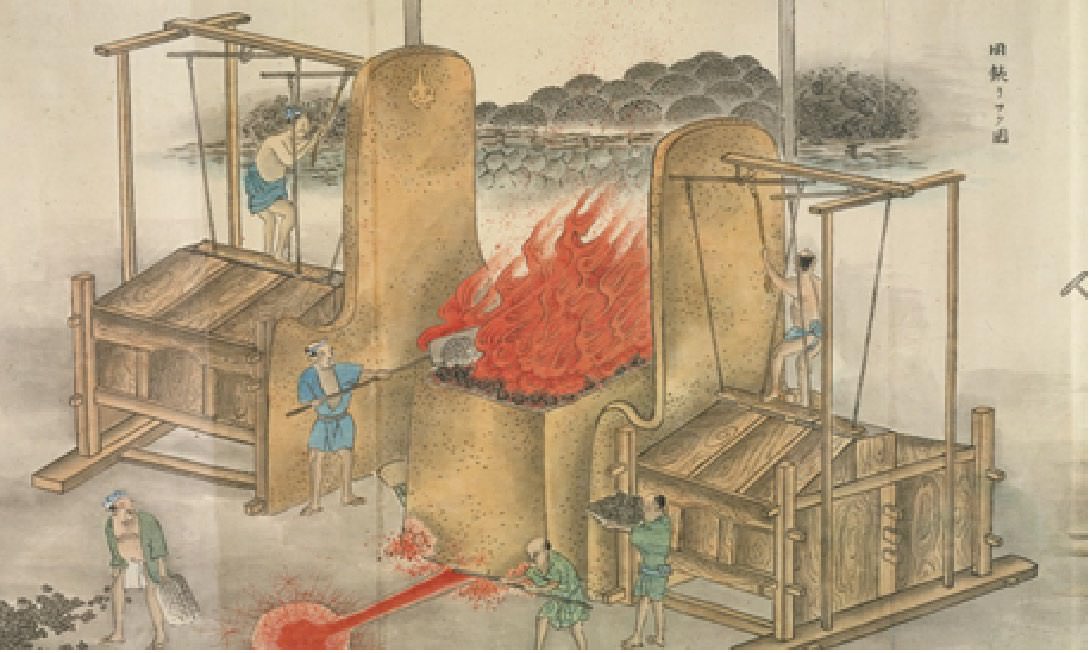

Izumo Province is delimited by the mountains of Chūgoku in the south and the Shimane peninsula in the north, with the plains and lake lands of Lake Shinji and Nakaumi in its center. The expansion of the province’s industries in the Edo period owes much to the influence of this geographical context. The development of the tatara iron industry (named for the traditional foot-bellows used to stoke the smelting furnace) in the mountains of Chūgoku drew on the raw materials provided by the region’s iron sand and charcoal. Families of iron-smiths such as the Itohara and Sakurai families of Nita District, and the Tanabe Family of Iishi District, flourished under the patronage of Matsue Domain. Meanwhile, in the lowland areas of the central plains, the large-scale opening up of rice-farming land was moving forward in conjunction with the reclamation of lakes and marshes. The Yamamoto, the Kisa, the Kowata, and the Tezen are some of the great landowning families that prospered on the plains.

Courtesy of Shimane University Library Digital Archive Collection

http://da.lib.shimane-u.ac.jp/content/2316

Courtesy of Tokyo University Libraries of Engineering and Information Science & Technology

The Wealthy Farmers of Izumo

These families, as well as becoming important landowners, were also households who built their wealth by foraying into commerce and industry as well, much like the iron-smiths who engaged in the production and sale of iron. Families like the Kisa and the Kowata operated wholesale warehouses that shipped cotton, which became a key industry for Izumo Province from the latter half of the Edo period. For this reason, they occupied an elite position as “elder farmers” in their respective towns and villages. There, in addition to asserting their social influence as local worthies, they also played a role in bolstering local autonomy and domainal control by serving in official positions in the village federations that constituted local county districts.

Matsue Domain and the role of the Wealthy Farmers

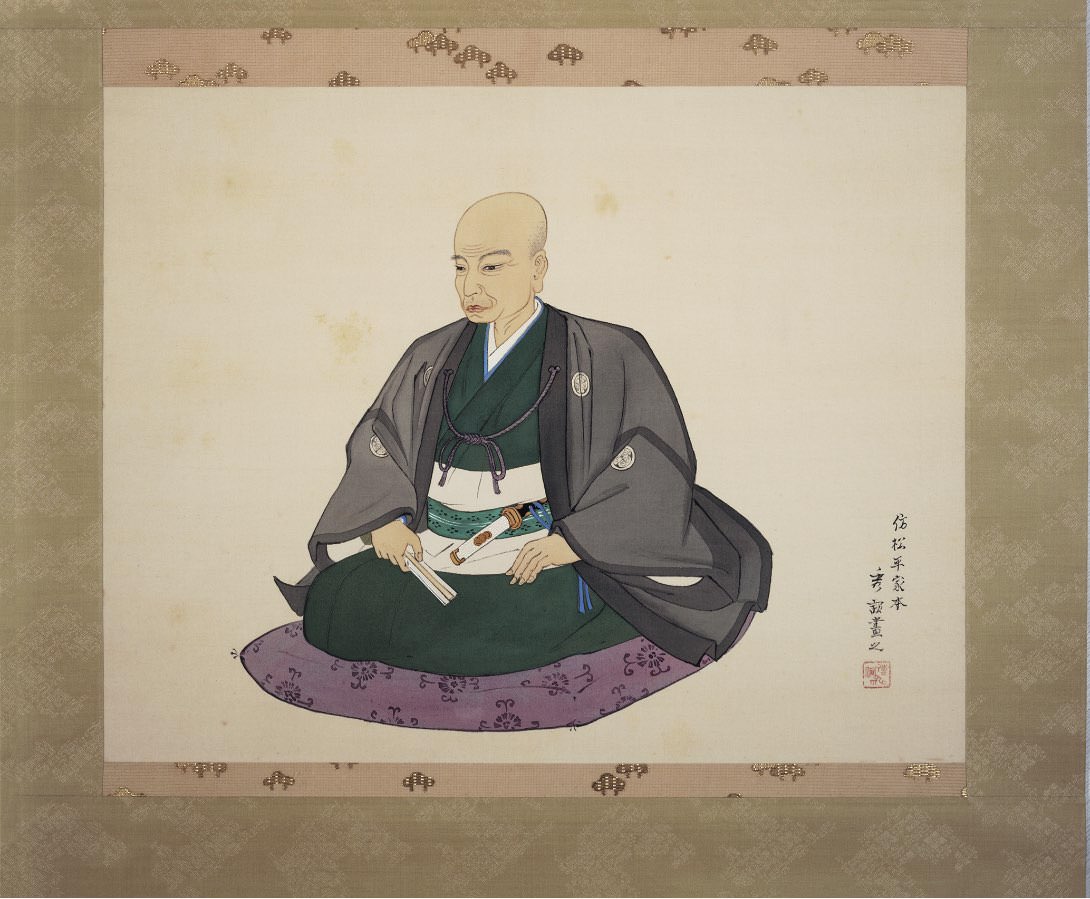

After the mid-eighteenth century, when the finances of Matsue Domain fell into decline, the role of these wealthy farmer families in contributing to the domain in economic terms, through donations commensurate with their means, became increasingly prominent. The rebuilding of the domain’s finances during the second half of the 18th century could also never have been accomplished without the assistance and cooperation of these wealthy farmers. In acknowledgement of these contributions, the domain responded by providing special treatment to the wealthy farmers, notably in the handling of their social status. Lord Harusato in particular observed the custom of “alternate attendance” in Edo (a practice whereby daimyō were required to maintain households in the Tokugawa capital where they would spend alternate years). In years when he was resident in Izumo, he would frequently tour the province under the pretext of visiting the grand shrine of Izumo Taisha and Hinomisaki Shrine, practicing falconry, and making forays into the innermost reaches of Izumo. On such occasions, he would often stay with wealthy local farmers, using their private residences as a headquarters for his own retinue.

The Historical Background of the Transmission of

Arts and Crafts

Such opportunities were an honor for the wealthy farmers who played host to the lord of the domain. They also led to cultural exchanges with Lord Harusato, a renowned practitioner of tea ceremony (in which context he was known under the name Fumai), as well as with his younger brother Nobuchika, a frequent companion on his elder brother’s tours and a noted haiku poet under the pen name Sessen. This also means that the wealthy farmers were under social pressure to master the cultural attainments that were befitting of their economic clout, the better to host the daimyō and the other samurai of Matsue domain in his retinue.

A consummate master of the tea ceremony, Lord Harusato (Fumai) built over the course of his lifetime a fine collection of tea utensils filled with specimens of the finest workmanship. He also sponsored the training of Izumo artisans such as the master joiner Kobayashi Jodei, the lacquerer Kojima Shikkosai, and the potter Nagaoka Sumiemon. The transmission of some of the articles from Lord Fumai’s collection and works by these artisans to the Wealthy Farmers households likely derives from circumstances such as those described above. After the domain system was abolished in 1871, the fact that Matsue Domain was able to call on these families to buy up Lord Fumai’s collection of tea utensils and ensure that it would remain in Izumo is surely owed to the long-lasting cultural involvement between them and the lords of the domain.